Infant distress during vehicular travel manifests as crying, fussing, and general unease. This common behavioral pattern can arise from various factors, including motion sickness, discomfort, or feelings of confinement within the car seat.

Addressing this behavior is important for both infant well-being and driver safety. Strategies employed to mitigate this distress have evolved over time, ranging from distraction techniques to modifications in vehicular environment and travel routines. A calm infant contributes to a more focused and less stressed driver, thereby reducing the risk of accidents.

The subsequent discussion will explore the underlying causes of infant discomfort in vehicles, practical strategies for soothing and calming the infant, and adjustments to travel arrangements that can help minimize this distress.

Mitigating Infant Distress During Car Travel

The following outlines practical strategies to minimize infant discomfort during vehicular transport, promoting a calmer and safer travel experience.

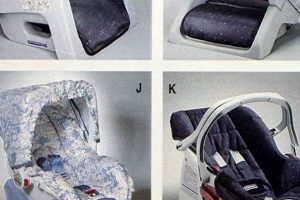

Tip 1: Optimize Infant Comfort: Ensure the car seat is appropriately sized and correctly installed according to manufacturer guidelines. Adjust straps for a snug, yet not restrictive, fit. Consider padding or inserts to enhance cushioning.

Tip 2: Regulate Environmental Conditions: Maintain a comfortable cabin temperature. Utilize window shades to minimize direct sunlight exposure. Ensure adequate ventilation to prevent stuffiness.

Tip 3: Strategic Timing of Journeys: Plan travel around the infant’s sleep schedule whenever feasible. A drowsy infant is more likely to remain calm throughout the journey. Avoid scheduling car trips during peak fussiness periods.

Tip 4: Introduce Familiar Sounds: Play soothing music or white noise to mask external disturbances. Consider using a portable sound machine specifically designed for infants. Test sound levels beforehand to prevent overstimulation.

Tip 5: Offer Distractions: Provide age-appropriate, soft toys or books to occupy the infant’s attention. Introduce new items sparingly to maintain novelty. Avoid toys with small, detachable parts.

Tip 6: Implement Short, Frequent Stops: Schedule regular breaks to allow the infant to stretch, move, and experience a change of scenery. Utilize rest stops or designated areas to ensure safety. Limit stop durations to prevent disrupting the infant’s routine.

Tip 7: Consider a Travel Mirror: Install a mirror that allows the driver to monitor the infant without turning around. Visual reassurance can help the driver anticipate and address potential issues before they escalate.

Implementing these strategies consistently may contribute to a reduction in infant distress during car travel, promoting a more peaceful environment for both the infant and the driver.

The next section will address underlying medical conditions that may contribute to travel-related discomfort and when to seek professional medical advice.

1. Motion Sensitivity

Motion sensitivity is a significant factor contributing to infant distress during vehicular transport. It refers to the heightened susceptibility of some infants to the physical sensations of movement, which can trigger a cascade of physiological responses resulting in discomfort and aversion to car travel.

- Vestibular System Immaturity

The vestibular system, responsible for balance and spatial orientation, is not fully developed in infancy. This immaturity can lead to an exaggerated response to motion stimuli, such as acceleration, deceleration, and turns. The resulting sensory overload can manifest as nausea, dizziness, and general unease, leading the infant to associate these negative sensations with the car environment.

- Sensory Conflict

Motion sensitivity can stem from a conflict between the visual and vestibular senses. When an infant is restrained in a car seat, the visual input may indicate a stationary environment, while the vestibular system detects movement. This sensory mismatch can trigger disorientation and discomfort, contributing to the development of aversion to car travel.

- Gastrointestinal Effects

Motion can stimulate the vagus nerve, which connects the brain to the digestive system. This stimulation can lead to gastrointestinal disturbances, such as nausea, vomiting, and increased salivation. These physical symptoms further reinforce the negative association with car travel, intensifying the infant’s aversion.

- Psychological Association

Repeated experiences of discomfort during car travel can lead to a learned association between the car and negative sensations. This psychological association can result in anticipatory anxiety and distress even before the car journey begins. The infant may begin to cry or fuss simply at the sight of the car seat or the act of being placed in it.

The complexities of motion sensitivity in infants underscore the importance of employing strategies that minimize sensory conflict and mitigate gastrointestinal effects. Addressing motion sensitivity, therefore, is crucial in creating a more positive and comfortable car travel experience, reducing the likelihood that the infant will develop a strong aversion to being in the car.

2. Confinement Discomfort

Confinement discomfort represents a significant factor contributing to infant aversion to car travel. The inherent limitations of space and restricted movement within a car seat can trigger negative reactions in infants, leading to distress and a general dislike of being in the car.

- Limited Motor Skills Expression

Infants possess a natural inclination to explore their environment through movement. Car seats, designed for safety, inherently restrict this movement. This limitation frustrates the infant’s developmental drive to kick, reach, and generally explore their physical capabilities, fostering discomfort and restlessness.

- Spatial Restriction and Claustrophobia

The confined dimensions of a car seat can induce feelings akin to claustrophobia in some infants. While not a clinical diagnosis, the sensation of being physically restricted can trigger anxiety and agitation, particularly in infants with a heightened sensitivity to their surroundings.

- Postural Constraints

Prolonged periods in a fixed posture can lead to muscle stiffness and discomfort. Infants lack the ability to adjust their seating position independently, exacerbating the discomfort associated with being confined to a single posture for extended durations. This lack of postural flexibility contributes significantly to overall distress.

- Visual Field Restriction

Car seats often limit the infant’s field of vision, restricting their ability to observe and engage with the external environment. This lack of visual stimulation can lead to boredom and frustration, further contributing to confinement discomfort and a negative association with car travel.

The multifaceted nature of confinement discomfort underscores its critical role in the phenomenon of infant aversion to car travel. Addressing these specific discomforts through modifications to car seat design, strategic use of breaks, and provision of appropriate stimulation can significantly mitigate the negative experiences associated with car journeys, thereby reducing infant distress.

3. Sensory Overload

Sensory overload, characterized by excessive stimulation of an infant’s sensory systems, represents a pivotal factor contributing to negative associations with vehicular travel. This phenomenon arises when the infant’s capacity to process incoming stimuli is exceeded, leading to distress and aversion to the car environment. Understanding the facets of sensory overload is crucial in mitigating its impact.

- Auditory Stimulation

Vehicular environments are often characterized by a cacophony of sounds, including engine noise, traffic sounds, radio broadcasts, and conversations. These auditory stimuli, often unpredictable and varying in intensity, can overwhelm the infant’s auditory processing system, leading to agitation and discomfort. For example, sudden loud honking or the persistent drone of the engine may induce heightened anxiety and crying.

- Visual Stimulation

The rapid passage of scenery, flashing lights from other vehicles, and varying light levels within the car create a visually complex environment. The infant’s developing visual system may struggle to process this constant stream of changing visual input, resulting in visual fatigue and disorientation. This can manifest as fussiness and an unwillingness to maintain eye contact.

- Tactile Stimulation

The car seat itself, while designed for safety, can contribute to tactile overload. The texture of the fabric, the pressure of the straps, and the limited ability to adjust position can create a constant source of tactile stimulation. Furthermore, temperature fluctuations within the vehicle can add to the tactile discomfort, leading to increased irritability.

- Vestibular Input

The constant motion of the vehicle stimulates the vestibular system, responsible for balance and spatial orientation. While some infants may tolerate this motion, others experience it as disorienting and unsettling. The combination of linear acceleration, deceleration, and turning can overwhelm the infant’s vestibular system, leading to nausea, dizziness, and a general feeling of unease.

The convergence of these auditory, visual, tactile, and vestibular inputs creates a sensory-rich environment that can easily overwhelm the infant’s limited processing capacity. This sensory overload results in distress and a negative association with car travel, thereby contributing to the aversion commonly observed in infants. Mitigating sensory overload, therefore, is paramount in creating a more positive and comfortable vehicular experience.

4. Routine Disruption

Routine disruption, characterized by deviations from an infant’s established daily schedule, significantly contributes to distress during car travel. The predictability of routines provides infants with a sense of security and control over their environment. Car journeys often necessitate alterations to these routines, resulting in discomfort and aversion.

- Sleep Schedule Alterations

Infants thrive on consistent sleep schedules. Car travel frequently requires deviations from established nap times, leading to overtiredness and increased irritability. An infant deprived of adequate sleep is more likely to exhibit distress during the journey, associating the car with discomfort and sleep deprivation. Example: Scheduled car rides that cross over nap time are likely to increase fussiness in the car.

- Feeding Schedule Irregularities

Regular feeding intervals are essential for maintaining an infant’s comfort and satiety. Car journeys may disrupt these intervals, leading to hunger and frustration. An infant experiencing hunger during travel is more prone to crying and agitation, reinforcing negative associations with the car environment. The stress caused by such irregularity will lead to baby distress.

- Environment Inconsistencies

Infants derive comfort from familiar environments. Car interiors, with their unfamiliar sights, sounds, and smells, represent a significant departure from the infant’s accustomed surroundings. This environmental inconsistency can trigger anxiety and distress, contributing to a negative perception of car travel. For example, a new car smell can be too strong and trigger crying.

- Daily Activity Interruption

Established daily activities, such as playtime or bath time, provide stimulation and comfort. Car journeys interrupt these activities, depriving the infant of familiar routines and sensory experiences. This disruption can lead to boredom, frustration, and an overall sense of unease, contributing to aversion to car travel. A simple walk in the park that’s skipped due to traveling can cause distress to the infant.

The outlined facets underscore the profound impact of routine disruption on infant comfort during car travel. Mitigating the effects of these disruptions through careful planning, strategic scheduling, and provision of familiar comforts can significantly reduce infant distress, fostering a more positive association with vehicular transport and help the baby.

5. Communication Inability

Infant communication inability represents a fundamental factor underlying distress during car travel. The limited capacity of preverbal infants to articulate discomfort, fear, or other negative sensations intensifies the challenges associated with identifying and addressing the causes of vehicular aversion. This inability transforms potentially minor issues into significant sources of distress, directly contributing to the association of negative emotions with the car environment. For instance, an infant experiencing discomfort from a tag on clothing or being too warm cannot verbally communicate this sensation, leading to escalating cries that are often misinterpreted or addressed inadequately. This misinterpretation then reinforces a negative association with being in the car.

The absence of clear communication channels necessitates heightened parental observation and interpretive skills. Parents must rely on subtle cues, such as facial expressions, body language, and the specific characteristics of crying, to decipher the infant’s needs. However, the complexity of infant cues and the inherent challenges of driving simultaneously often impede accurate and timely assessment. Consider a scenario where an infant’s crying stems from motion sickness; without verbal communication, parents may incorrectly attribute the distress to hunger or boredom, leading to ineffective interventions and prolonged discomfort. Consistent misinterpretations can lead to increased frustration in the baby, further solidifying negative experiences in a car.

Addressing the challenge of communication inability requires a multifaceted approach. Prioritizing pre-trip comfort checks, implementing frequent stops to assess the infant’s well-being, and creating a calm and predictable car environment are critical steps. Furthermore, parents can benefit from education on infant communication cues and strategies for effective response. By acknowledging and proactively managing the limitations imposed by communication inability, it becomes possible to mitigate infant distress during car travel, fostering a more positive association with vehicular transport. The baby is not crying just to cry; there is always a reason.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following addresses common queries regarding infant distress during vehicular transport, providing succinct and evidence-based responses.

Question 1: Is it normal for infants to exhibit distress during car journeys?

Yes, infant distress during car journeys is a prevalent phenomenon. The combination of motion, confinement, and sensory stimulation can overwhelm an infant’s developing nervous system, leading to crying and fussiness.

Question 2: What are the primary causes of infant aversion to car travel?

Key causes include motion sensitivity, confinement discomfort, sensory overload (noise, light, temperature), routine disruption (sleep, feeding), and the infant’s inability to effectively communicate their needs.

Question 3: How can parents mitigate motion sickness in infants during car travel?

Strategies include ensuring adequate ventilation, limiting visual stimulation (window shades), scheduling travel during sleep times, and, in consultation with a pediatrician, considering age-appropriate motion sickness remedies.

Question 4: At what age should concerns about infant car distress be escalated to a medical professional?

Persistent or severe distress, especially if accompanied by vomiting, fever, or other signs of illness, warrants immediate medical consultation. Furthermore, any concerns about car seat fit or installation should be directed to certified child passenger safety technicians.

Question 5: Are there car seat features that can help minimize infant discomfort?

Select car seats with breathable fabrics, adjustable recline positions, and adequate head support. Ensure the car seat is appropriately sized for the infant’s age and weight and is installed correctly according to the manufacturers instructions.

Question 6: How does routine disruption impact infant comfort during car journeys?

Disruptions to established sleep and feeding schedules can significantly increase infant distress. Attempt to align travel times with the infants natural sleep patterns and ensure access to feeding opportunities during breaks.

Addressing infant aversion to car travel necessitates a multifaceted approach, integrating proactive comfort measures with vigilant monitoring of the infant’s well-being.

The subsequent section will outline specific product recommendations and resources to aid in minimizing infant discomfort during car journeys.

Addressing Infant Car Travel Aversion

The phenomenon of “baby hates car” stems from a confluence of factors including physiological sensitivities, environmental influences, and disrupted routines. Effective mitigation requires a comprehensive understanding of these elements and the implementation of proactive strategies aimed at minimizing discomfort and sensory overload. Consistent application of these strategies may yield a more positive vehicular experience for the infant.

Persistent infant distress during car travel warrants further investigation. Caregivers are encouraged to consult with pediatric professionals to rule out underlying medical conditions and to explore personalized solutions. Prioritizing infant comfort and safety remains paramount in ensuring positive developmental outcomes and promoting safe vehicular transport.